World

World University Rankings 2025: shifting patterns

Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2025

If the World University Rankings were a person it would now be allowed to drink in the US. In this 21st edition we are raising a glass to the biggest table yet, with more than 2,000 institutions ranked and 115 countries represented for the first time. Cheers!

This year sees some interesting trends, including the University of Oxford reigning supreme with the longest run in the top spot ever, though a drop in reputation for UK universities on the whole.

Elsewhere, it’s all change for elite US universities, which are switching positions; Australia appears to be losing ground; the Netherlands could be one to watch; and we have a more diverse top 200.

There are also seven countries that are ranked for the first time this year: Bahrain, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mongolia, Paraguay, Rwanda, Syria and Uzbekistan.

Oxford and the UK

The University of Oxford has retained its number one spot for the ninth year in a row, making it the longest reign in the history of the rankings (the California Institute of Technology was previously top for five years and, before that, Harvard led for eight).

Oxford’s industry score (based on industry income and, since last year, patents) has significantly increased in recent years, as has its teaching environment score. But when comparing its performance against other institutions in the top five, it stands out for its international outlook (particularly proportion of international students and international co-authorship).

The UK sector has less positive news, however, when it comes to reputation. Among the 12 British universities in the global top 100, the average teaching and research reputation scores have dropped for the second year in a row.

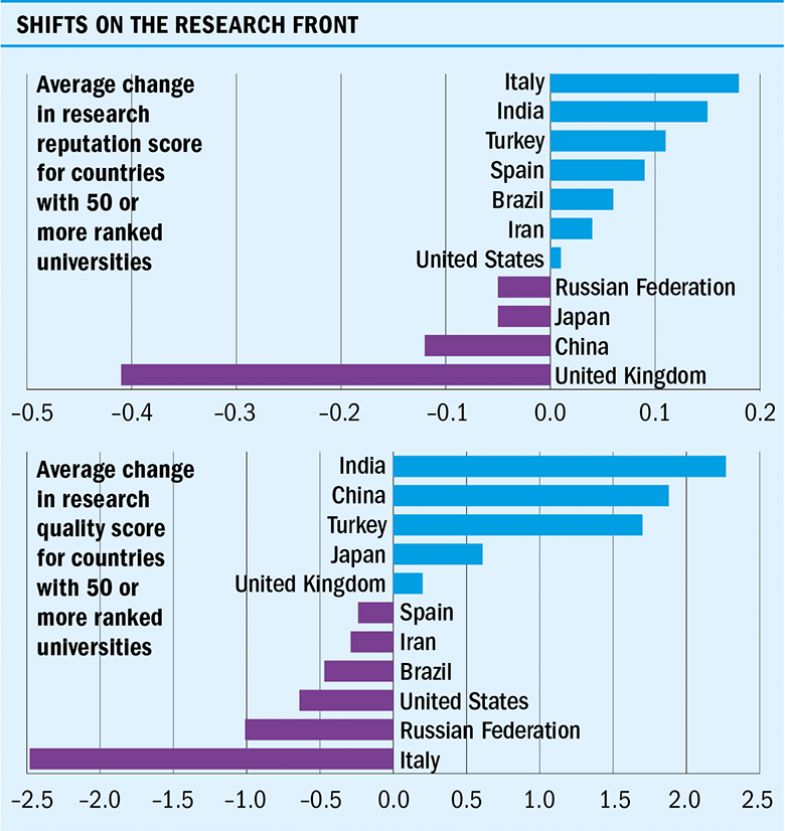

Among large countries – the 11 nations with at least 50 institutions ranked this year and last year – the UK recorded the worst year-on-year decline in research reputation.

Victor Melatti, data scientist at Times Higher Education, says that part of the reason for the UK’s drop is that the reputation survey has expanded in recent years, with scholars from more countries participating, leading to a broader distribution of votes.

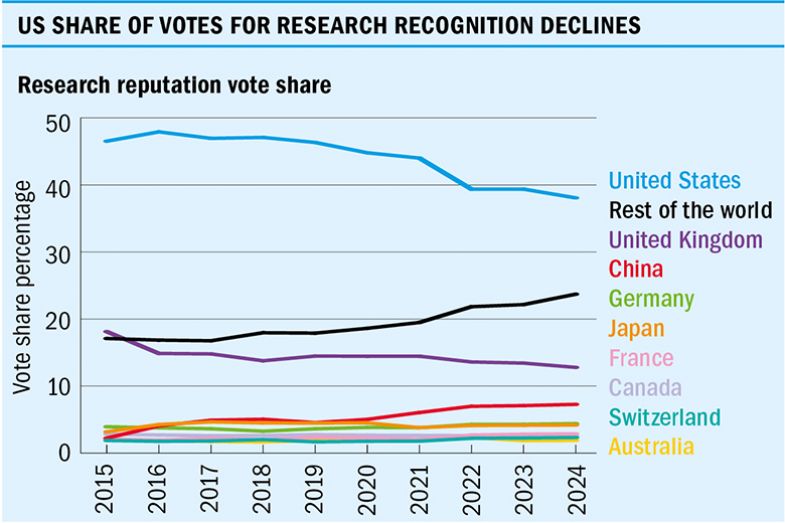

The survey received votes from more than 93,000 academics in the past two years combined, up from about 22,000 in 2019 and 2020. UK universities received 19 per cent of votes (for teaching and research combined) in the survey in 2016, compared with 15 per cent today; the US has seen an even steeper long-term decline, from 47 per cent to 32 per cent.

However, the more significant year-on-year drop for the UK in research reputation, compared with the US, suggests there might be other factors at play too. And this decline may worsen in future years given that UK universities are facing a funding crisis, with one in three making redundancies in a climate of high inflation, frozen English tuition fees and declining international enrolments.

US movement at the top

US universities continue to dominate the top 10, but there have been shifts in their positions. Stanford University has dropped from second to sixth, its lowest position since 2010, driven by a fall in its score for teaching from 99.0 to 97.5 and slightly lower scores for research environment and international outlook. Digging deeper, the drop under teaching is due to a lower score for doctorate-to-staff ratio; it has also declined when it comes to research income and productivity, and international staff and co-authorship.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – now the highest-ranked US university at second place, its best-ever performance – Harvard University, Princeton University and the University of California, Berkeley have all moved up the ranking.

MIT and Princeton are proving to be dark horses, with the data revealing steady improvements in their positions since 2016. Princeton appears to have improved where Stanford declined: with better scores under doctorate-to-staff ratio as well as doctorate-to-bachelor ratio. It has also improved in terms of industry income, with a score of 93.7 this year, up from 90.2 last year. Meanwhile, MIT has progressed in all metrics over the past 10 years.

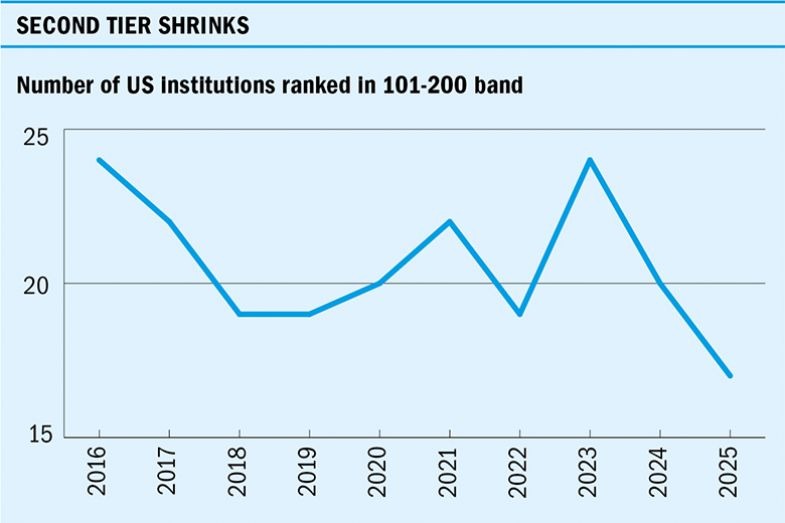

Overall, the US has slightly improved its representation in the top league, with 38 institutions ranked in the top 100, up from 36 last year. However, there appears to be a hollowing out of the next tier – those ranked between 101 and 200. There are now only 17 US universities in this group, its lowest number ever. These institutions have suffered drops in teaching reputation, research productivity and three metrics relating to research quality.

Among large countries – the 11 nations with at least 50 institutions ranked this year and last year – the US recorded the third worst year-on-year decline in average research quality score.

A more diverse top 200

For the past four years, the number of countries represented in the top 200 has remained steady at 27, but this year it has risen to 30.

One of the new countries is the United Arab Emirates, represented by Abu Dhabi University, the first institution in the country to reach the top 200. It is ranked joint 191st, up from the 251-300 band last year. The university has higher scores in the teaching environment, research environment and research quality pillars.

In 2021, the US had 59 universities in the top 200; this has now dropped to 55. The UK’s count has also decreased, from 29 to 25, and Germany’s from 21 to 20. China and Japan are the only countries to increase their representation in the top 200 by more than one during this period, by six and three respectively. China now has 13 and Japan has five.

The University of São Paulo in Brazil has also just cracked the top 200 at joint 199th, the institution’s best performance since 2013. The main factor behind its rise is its improvement in industry (income and patents).

Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), the country’s joint third-highest ranked institution, also improved its position, rising from band 801-1,000 to 601-800 this year. The three others in Brazil’s top five have stayed in the same bands. Brazil now has 61 universities ranked, with five institutions added this year. Compared with the rest of South America, Brazilian universities have the highest average score in the teaching, research environment and industry pillars.

This could represent a turning point for the country’s higher education system. While it continues to suffer from years of underfunding, the ousting of anti-intellectual Jair Bolsonaro as president nearly two years ago might be starting to have an impact.

Decline in Oceania

For the second year in a row, Australia’s elite universities have slipped down the rankings; the top five are all ranked lower than they were last year. The University of Melbourne, the country’s highest-ranked institution, has dropped from 37th to 39th; Monash University from 54th to joint 58th; the University of Sydney from 60th to 61st; Australian National University from 67th to joint 73rd; and the University of Queensland from 70th to 77th.

In 2021, Australia had 12 universities in the top 200, but it now has 10.

Looking at the average pillar scores of Australia’s top 10 universities, we can see that the drops are driven by reductions in the teaching and research environment pillars. The average teaching score for these institutions is 46.9, compared with 48.2 last year, and the average for research environment is 57.4, compared with 59.0 last year.

Of Australia’s total 38 universities ranked, four have gone up, 17 down, 16 remain unchanged and one was not ranked last year.

Experts point to the loss of international student revenue, due to border closures during the pandemic and some of the world’s longest lockdowns, as a key reason for the decline.

However, Merlin Crossley, deputy vice-chancellor at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Sydney, is confident that the country’s performance will recover.

“In the last 15 years, Australian universities have shone on the world stage. Our top institutions have bounced back after Covid and the rapid return of international students is temporarily throwing out some of the ratios and reducing our scores, though the actual quality in our system has been sustained,” he says. “I’m optimistic that the momentum to invest in staff and research will continue in Australia and we’ll keep up with our impressive Asian neighbours.”

Neighbouring New Zealand is also struggling. The University of Auckland, the country’s top performer, has dropped from joint 150th to joint 152nd. Of New Zealand’s eight universities in the ranking, three have declined and five have retained their positions.

All change in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, eight of the 12 institutions ranked have dropped down the table, but the other four have risen.

The country’s highest performer, Delft University of Technology, has slipped out of the top 50, dropping from 48th to joint 56th. Conversely, the country’s second-highest performer, the University of Amsterdam, has risen from 61st to joint 58th. Erasmus University Rotterdam has dropped out of the top 100, from joint 99th last year to joint 107th.

The change for Delft University of Technology was driven by a reduced score for teaching. Its score for international outlook has improved, but the Netherlands could be a country to watch when it comes to global links. The new coalition government, with the far-right Party for Freedom now the largest party, has proposed restrictions on international students and researchers, including limitations on English-language instruction and higher tuition fees for students from outside the European Union.